May Nature Almanac: Black-headed Grosbeaks arrive in full song from Mexico

By Scott Severs, with Stephen Jones and Ruth Carol Cushman

May 2023

As spring migration reaches a climax, many birders in Front Range towns have the opportunity to see transient bird species that stop over in the plains for a day or two before heading to the foothills and mountains of the Rockies. One colorful songbird that we are happy to catch on its migration travels is the Black-headed Grosbeak.

Grosbeaks, as their name implies (gros, from Latin, meaning “thick”), have huge seed-cracking bills perfect for splitting apart even the toughest fruit and seeds. Black oil sunflower seeds are one of their favorite foods at bird feeders. Bird banders must be wary when handling Black-headed Grosbeaks, as those powerful mandibles can inflict painful bites. These bills are perfect for foraging on insects with hard exoskeletons such as beetles and grasshoppers.

Male Black-headed Grosbeak. Photo by Helmy Oved.

Female Black-headed Grosbeak. Photo by Rich Leche.

Male Black-headed Grosbeaks remind some people of orioles as they are similarly colored and patterned. Their heads are coal black, breasts bright orange-brown, and they have black and white wings and tails. Yet it is the grosbeak's massive straw-colored beak that distinguishes it from the oriole. The oriole has a long black beak that could hardly dent a tree seed. Instead of having a black head, the crown of the female Black-headed Grosbeak is adorned with a pattern of black and white stripes, giving her a sparrow-like appearance. Black-headed Grosbeaks are related to Northern Cardinals both belonging to the family Cardinalidae. Large songbirds, grosbeaks are about the size of a Red-winged Blackbird.

Upon their return from Mexico, adults pour out energetic song to announce the start of the nesting season. The rich warbled melody interspersed with trills reminds us of a speeded up and exceptionally sweet robin's song. Glenn Cushman says it sounds like an hysterical robin! Upon the appearance of a female, the male may launch himself into a courtship display and fly over her as she sits, watches, and listens. Grosbeaks often communicate with a sharp “peek” call.

In Colorado, Black-headed Grosbeaks prefer deciduous woodlands along streams, moist aspen groves, and shrubby thickets from the foothills to 10,000 feet. Nesting activity commences in early May when males and females weave messy nests of small twigs, tiny rootlets, and grasses usually in forks of willows or chokecherries. Females produce 3 to 4 brown spotted bluish-white eggs that both adults incubate for nearly two weeks. Nestlings leave the nest about 12 days later. Fledglings remain with the adults for a few more weeks and the adults can be seen giving incessantly begging youngsters a bill full of mashed-up seeds or insects. Grosbeaks can be attracted into yards by plantings of chokecherry, ash, aspen, and serviceberry. Grosbeaks will enthusiastically splash in water features, such as birdbaths or shallow ponds.

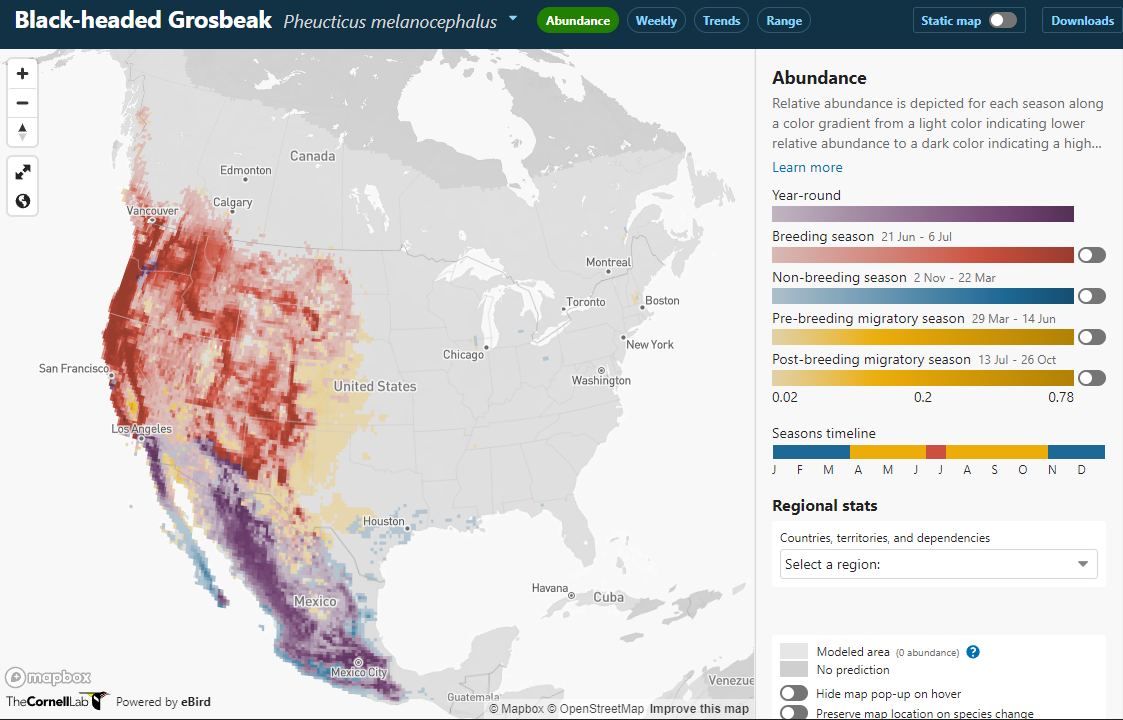

Black-headed Grosbeaks breed in the western US and Mexico. In the non-breeding season, they migrate out of Colorado and the more northern portions of the breeding territory.

Unlike Evening Grosbeaks, Black-headed Grosbeaks leave Colorado for the winter, migrating to Mexico where burning and clearing of critical habitats may negatively impact this and other summer-resident Colorado birds in the future. Monarch butterflies, eaten by few birds due to their toxic nature, are foraged on by grosbeaks where they winter together in central Mexico. In the Boulder area, good places to see Black-headed Grosbeaks this spring include Gregory Canyon, Sawhill Ponds, and Boulder Creek.

Other May Events

Red-tailed and prairie (Swainson’s) hawks are attending and feeding nestlings.

Woodhouse’s (sheep) toad’s bleating “waaaaaaaaaa’ call peaks at local streams and ponds.

Green hedgehog cactus bloom their delicate chartreuse-colored flowers in shortgrass prairies.

A new generation of common green darner dragonflies migrates in from Mexico and Central America. They’ll breed here and the subsequent generation will head south in August and September.

Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep birth one or two lambs in isolated alpine hideaways. Always give them space for peace and solitude as they grow.