February Nature Almanac: Wandering Waxwings

By Scott Severs, with Ruth Carol Cushman and Stephen Jones

February 2023

Our frigid early morning bird walk began just after sunrise, as we looked for some rare visitors to the Colorado Front Range. There had been many reports in the birding circles of these infrequent visitors - Bohemian Waxwings.

Bohemian waxwings have colorful wings and rusty undertail feathers to distinguish them from cedar waxwings. The waxy red tips of on the secondary feathers of waxwings come from carotenoids in their diet. Photo courtesy of Chris Petrizzo.

It’s once in many years when these unpredictable visitors make a journey from the Yukon and Alaska down into Colorado searching for native and ornamental fruits to sustain them through cold February nights. We began our search along Boulder Creek north of the University of Colorado campus where some had recently been seen.

Bohemian Waxwings have a circumpolar distribution and occasionally visit Colorado during the non-breeding season. Check out the interactive map of global abundance on eBird.

Bohemian Waxwings are larger cousins to the more commonly seen Cedar Waxwing that we have year-round in Boulder County. Bohemians are somewhat larger, about the size of a starling. They’re also a touch more colorful than Cedar Waxwings, with peach highlights around the black mask on their face, and rusty under-tail feathers. They also have more extensive yellow and white and wax markings on their wings, and like their cousin the cedar waxwing, a tail tip that looks like it’s been dipped in bright yellow paint. Both species have wonderful pointy crests that they can raise and lower at will.

Bohemian (L) and Cedar Waxwing (R) foraging along Clear Creek in Wheat Ridge, Colorado. Notice the color variation in the face, belly, and vent. Photo courtesy of Chris Petrizzo.

Waxwings are so named because of waxy highlights that appear on the secondary feathers on their wings. These colorful feathers have a unique red tip that appears to have been dipped and dried with a drop of red wax. These highlights are produced chemically by the bird’s metabolism, changing the carotenoids, red pigments, found in their berry meals into these colorful feather highlights. We once saw a flock of more than 100 Bohemian Waxwings land on a medium-sized juniper near Nederland. The birds quickly set up berry-brigades, passing the ripe juniper berries from one beak to another. Meanwhile, an enraged, territorial juniper (Townsend's) solitaire repeatedly dive-bombed the flock, to no avail.

European mountain-ash are one of many nonnative and native berry producing trees and shrubs sought out by bohemian waxwings. Photo by Stephen Jones.

The “bohemian” description matches their behavior well. Their need for fruit often leads them to wander hundreds of miles to find available food sources. Boulder County once held the annual Christmas Bird Count’s all-time highest record for Bohemian Waxwings in the continental United States — 11,284 individuals seen in 1987! That amazing total will unlikely happen again because, unfortunately, the species has undergone a decline of 55% from historic populations. Our last large invasion was in 2007. This year Boulder County hasn’t had as many as Denver and farther south where flocks of up to 800 birds are being reported!

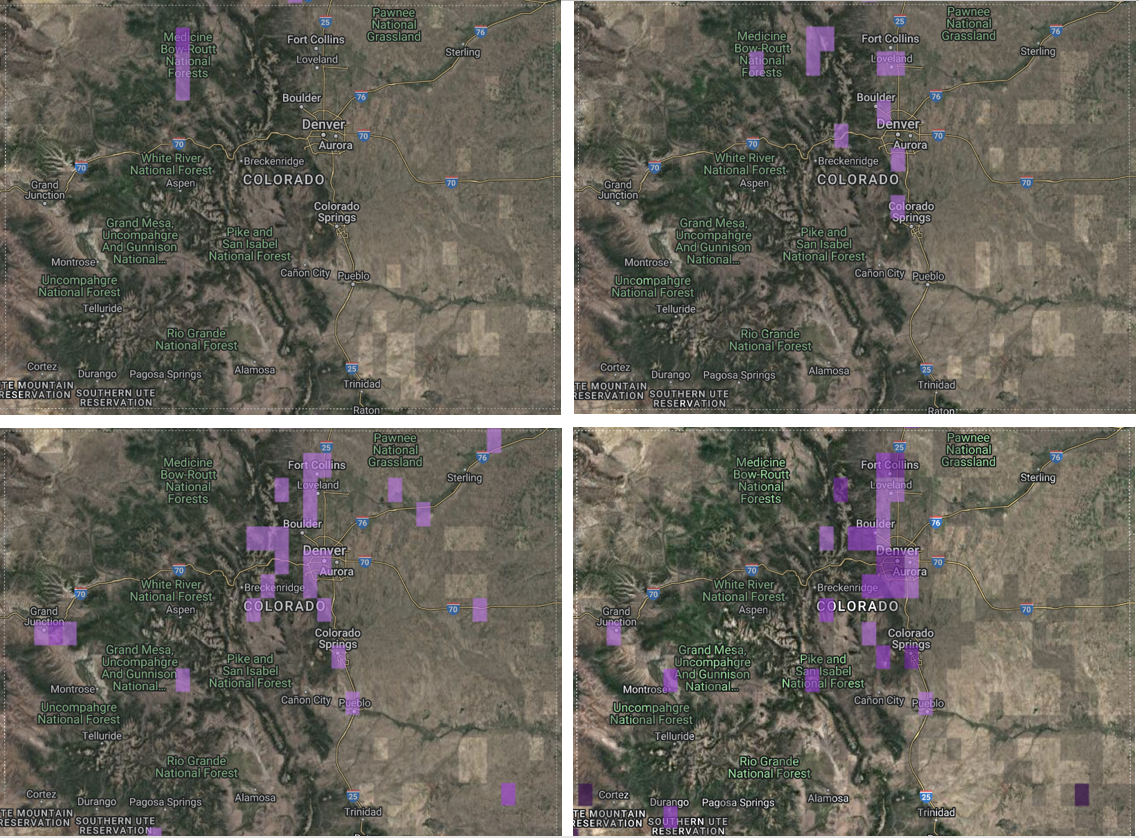

Reports to eBird of Bohemian Waxwings in Colorado. Top left to bottom right, 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023 (really only the first 25 days of 2023!). Darker purple indicates a higher frequency of encounters. Explore more on eBird range maps.

Alas, our bird walk ended with no sightings of Bohemian Waxwings, but we did see lots of other pleasant birds in small groups as one is prone to find this time of year. The older and diverse tree species make the University of Colorado campus a good birding destination in the middle of winter. There are still opportunities to see Bohemian Waxwings especially if you look in older neighborhoods with ornamental fruit trees. Good numbers have been reported along Clear Creek near Prospect Park and in the Wheat Ridge Greenbelt. It’s always worth checking large American Robin flocks to see if waxwings are present, as they share similar food preferences.

Other February Events

Bald Eagles and Great Horned Owls begin incubating eggs, often holding back several inches of February snow from the centers of their nests.

Many Canada and Cackling Geese have been found dead and frozen in the ice recently, apparently victims of avian influenza. We’ve observed Bald Eagles and Northern Harriers feeding on the carcasses and fear the contagion will spread to these raptors. Learn more about the impacts avian flu is having in Colorado and what to do if you see dead birds in this article from Colorado Field Ornithologists.

Snow Goose numbers peak in southeast Colorado. Check out the Snow Goose Festival in Lamar, CO on February 3-5, 2023. Can’t make the drive, look for white geese (Snow Goose and Ross’s Goose, or hybrids) in open fields throughout eastern Boulder County mixed in with flocks of Canada and Cackling Geese.

The first Mountain Bluebirds begin appearing in open space grasslands at the end of the month.

Aerial courtship of Common Ravens begins. Watch for pairs in close formation with fast shallow wingbeats and emitting low barking calls.